1. Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals in the Environment

Pharmaceuticals are now widely detected in natural and urban water systems around the world. Since the 1980s, monitoring programs have repeatedly found medicines—including antibiotics, painkillers, anti-epileptics, antidepressants, lipid regulators, and heart medications—in rivers, lakes, coastal waters, groundwater, and even treated drinking water. Their presence varies from place to place, depending on how much a community uses specific medicines and how effective its wastewater treatment systems are.

These substances typically appear in very low concentrations, but they can still impact ecosystems because they are biologically active by design. Studies show that one water sample may contain a mixture of many different pharmaceuticals at the same time. Among all drug categories, antibiotics are the most frequently detected worldwide, followed by common analgesics such as ibuprofen and diclofenac. Regions with high medicine use and strong monitoring programs—such as parts of Europe and Asia—report the highest detection rates.

Pharmaceuticals are commonly found in hospital wastewater, WWTP influent and effluent, surface waters, and occasionally in groundwater and drinking water. Their distribution changes with seasons, local consumption habits, and proximity to pollution sources.

2. Sources and Pathways of Pharmaceutical

2.1 Major Sources of Contamination

Pharmaceuticals enter the environment through both direct and diffuse routes. Major point sources include hospitals, wastewater treatment plants, and pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. Non-point sources include domestic sewage, agricultural runoff, livestock operations, aquaculture, and the improper disposal of unused medicines.

2.2 The Environmental Pathway

After being consumed by humans or animals, drugs undergo metabolic transformation—Phase I reactions (such as oxidation or hydrolysis) and Phase II reactions (such as conjugation). Both unchanged parent compounds and their metabolites are excreted and transported into sewage systems. Wastewater treatment plants can remove part of this load, but many pharmaceuticals pass through treatment and are released into the environment.

Once discharged, pharmaceuticals move through soil and water by leaching, sorption and desorption, chemical degradation, and microbial transformation. Their mobility depends largely on their solubility, polarity, dissociation constant (pKa), and how they partition between water and sediments.

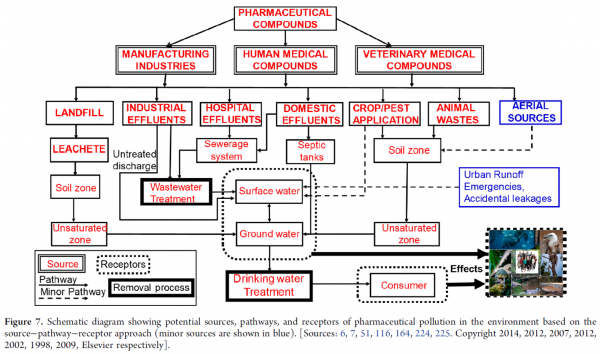

The widely used source–pathway–receptor framework helps explain how pharmaceuticals travel from human activities into rivers, soils, groundwater, and eventually drinking-water supplies. This model highlights the importance of understanding each step—from use and disposal to environmental transport—to effectively manage and reduce pharmaceutical contamination.

3. Conventional Wastewater Treatment and Control

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are major control points for pharmaceuticals because large quantities of these compounds reach sewage systems after human and veterinary use. WWTPs rely heavily on biological processes, which can degrade some pharmaceuticals while leaving others untouched.

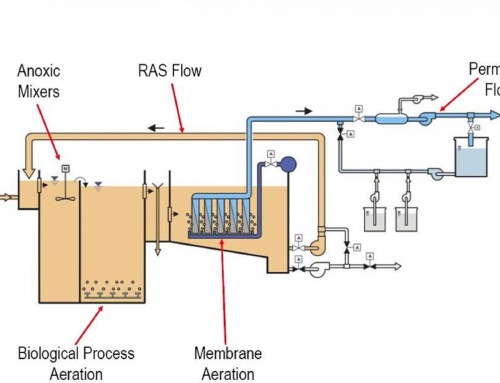

3.1 Conventional Biological Treatment Processes

The most common methods include activated sludge, trickling filters, aerated lagoons, anaerobic digestion, and stabilization ponds.

Pharmaceutical removal occurs through biodegradation and sorption onto sludge.

Compounds with high sorption potential often accumulate in sediments, while more persistent pharmaceuticals pass through the system. Removal efficiencies vary widely by drug type; the typical trend is:

Stimulants > metabolites > analgesics > antibiotics > anti-inflammatory drugs > lipid-regulators > NSAIDs > persistent pharmaceuticals

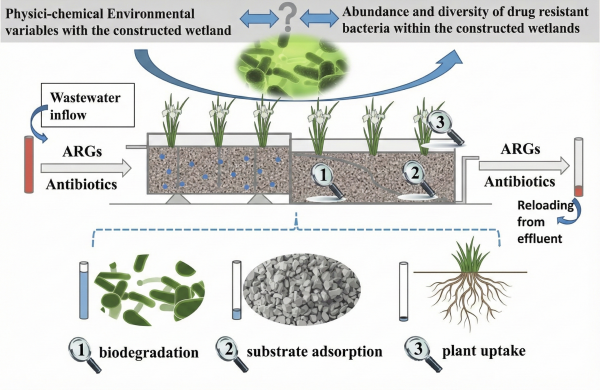

3.2 Constructed Wetlands

Constructed wetlands offer an eco-friendly, low-cost treatment option. They combine plant uptake, microbial activity, and soil sorption to remove pharmaceuticals.

They have several advantages:

- Good overall removal.

- Low energy use.

- Minimal operational requirements.

However, they require large land areas and long retention times, which limits their feasibility in dense urban regions.

4. Advanced Water Treatment Technologies (AWT) for Pharmaceutical Removal

Advanced treatment technologies achieve much higher removal efficiencies and are increasingly used to treat both drinking water and wastewater. Section 3.3 covers the most effective modern solutions.

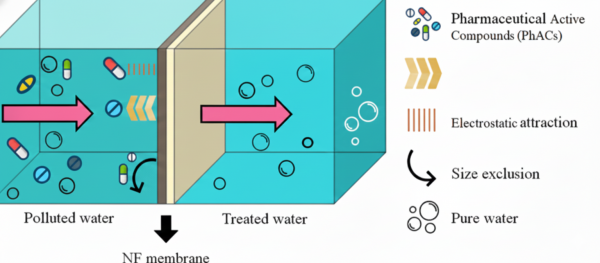

4.1 Nanofiltration (NF)

Nanofiltration membranes can remove over 90% of many pharmaceuticals. Their performance is governed by:

- Size exclusion (larger molecules cannot pass).

- Electrostatic repulsion between charged drugs and membrane surfaces.

- Hydrophobic interactions.

Removal efficiency depends on the drug’s size, polarity, and charge, as well as membrane properties and operating conditions.

For example, negatively charged pharmaceuticals such as sulfamethoxazole are rejected more effectively at higher pH values because ionization increases repulsion.

NF is widely studied due to its strong performance but must be operated carefully to avoid fouling.

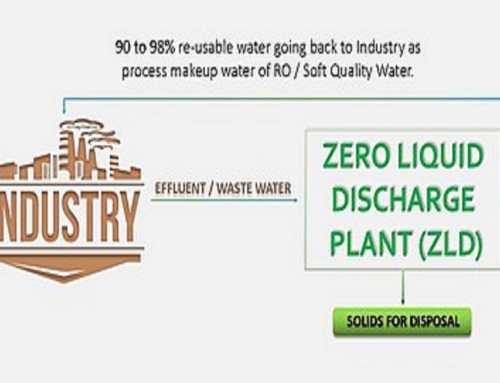

4.2 Reverse Osmosis (RO)

Performance depends on:

- membrane material

- pore size / molecular weight cutoff (MWCO)

- hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions between drugs and the membrane

Examples reported in the review include:

- 85% removal of certain NSAIDs from groundwater

- 95% removal in a German drinking-water plant using polyamide and cellulose acetate membranes

Limitations include fouling, sensitivity to oxidants, high operational costs, and the need for brine management.

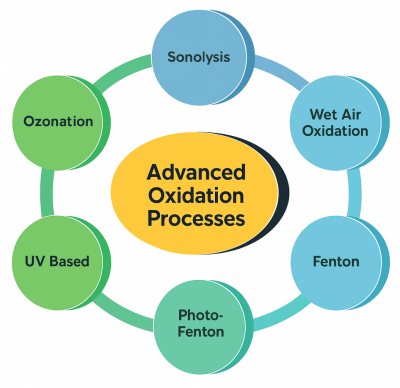

4.3 Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs)

AOPs use highly reactive radicals—especially hydroxyl radicals (•OH)—to degrade pharmaceuticals into simpler molecules. They are among the most efficient methods described in the article.

Common AOPs include:

- ozonation (O 3)

- UV/H2O

- O3/H2O2

- Fenton and photo-Fenton processes

- photocatalysis

- electrochemical oxidation

These methods achieve degradation levels up to 99% for many pharmaceuticals such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, carbamazepine, sulfamethoxazole, and 17α-ethinylestradiol. Photochemical AOPs often outperform standalone ozone treatment.

Challenges include energy demand and the formation of transformation byproducts.

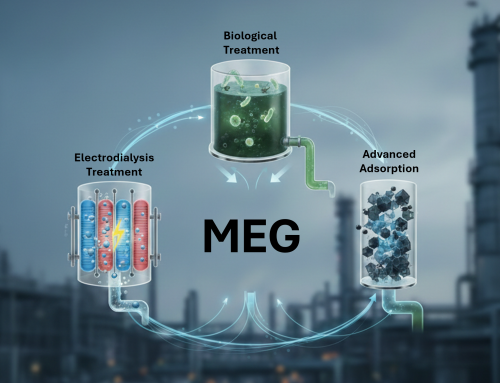

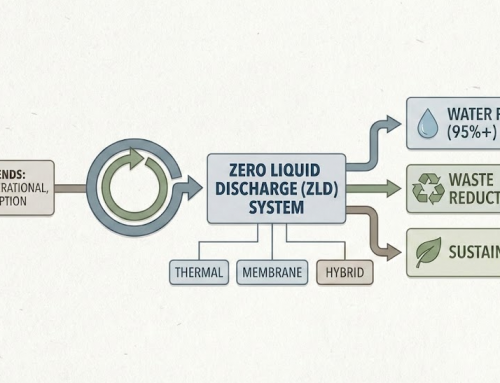

4.4 Combined and Hybrid Processes

Hybrid systems combine complementary processes to improve overall removal and reduce the formation of harmful byproducts.

Examples include:

- AOP + biological treatment

- AOPs first break down persistent pharmaceuticals

- biodegradability increases dramatically

- e.g., Fenton pretreatment boosts quinolone removal from 33% to 95%

- Adsorption + ozonation

- ozone destroys contaminants

- activated carbon captures intermediates

- overall removal 90–100%

- Photocatalysis + nanofiltration

- photocatalyst degrades pharmaceuticals

- NF removes catalyst particles and residuals

- RO + activated carbon

- activated carbon protects RO from fouling

- enhances long-term performance

These integrated treatment trains represent some of the most effective solutions for modern water and wastewater management.

4.5 Sorptive Removal (Activated Carbon & Other Adsorbents)

Sorption is one of the most widely used methods for eliminating pharmaceuticals in both drinking water and WWTPs. Activated carbon is especially effective due to its high surface area and strong interactions with organic molecules.

Pharmaceuticals are removed through:

- hydrophobic interactions

- pi–pi interactions

- electrostatic attraction

- hydrogen bonding

Biochar, clays, mineral sorbents, and engineered materials also show good performance.

Limitations include adsorbent saturation and the cost of regeneration or replacement.

Ion-exchange processes are discussed but noted to be largely ineffective for most pharmaceuticals.

The sources of the images and articles used to write this text are available in this downloadable file: Click here!